Search

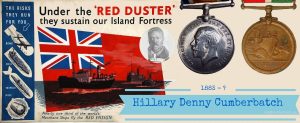

Jimmy Cumberbatch the first black player to play for England at rugby league. He played against France in 1937 and scored two tries for 6 points on his debut.

There was a place of worship on Sunny Bank. This was originally the Baptist Chapel and there was a large bath in the building for the baptising of their flock. Facing the road was Chapel House, and one day my mother passed the gate and she saw four dark eyes looking over the gate. They were two little black boys. They were the first black persons that she had ever seen. She told me how fast the two little boys could run, and speed was eventually essential in making their living, as when they grew up they both became famous Rugby League Stars, their names being James (Jimmy) and Valentine Cumberbatch. Valentine became an excellent three quarter back for Barrow in the 1930’s and early 1940’s, and Jimmy was the first black player to play Rugby League for England.

History of Lindal & Marton Brian Edge’s Memories: http://lindal-in-furness.co.uk/Features/BrianEdge/brianedge.htm Visited: 25 Jun 2022

James Haywood Jimmy Cumberbatch

Jimmy Cumberbatch the first black player to play for England at rugby league. He played against France in 1937 and scored two tries for 6 points on his debut.

James Jimmy Cumberbatch scores two tries in his debut against France in 1937

James Jimmy Cumberbatch scores two tries in his debut against France in 1937

Viv Anderson broke through as the first black player to represent England at football in 1978, but rugby league had already beaten this achievement by more than forty years when Jimmy Cumberbatch ran out for England against France in 1937

The Glory of their Times Edited by Phil Melling, Tony Collins

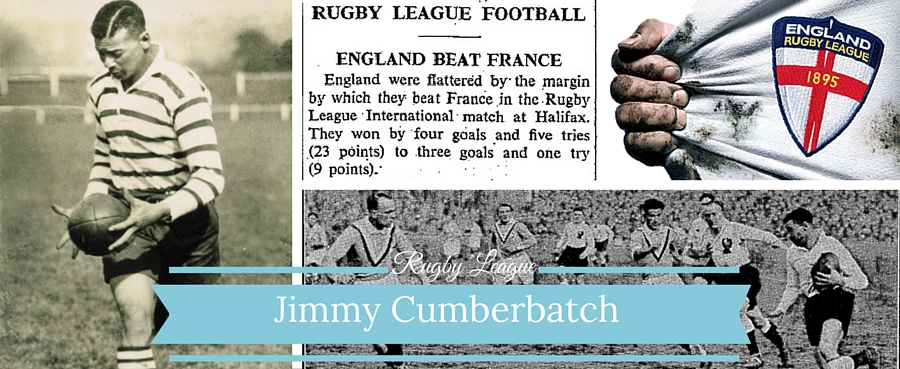

ENGLAND BEAT FRANCE

Jimmy Cumberbatch the first black player to play for England at rugby league played against France at Thrum Hall, Halifax, England on 10 April 1937 in the European Championship 1936/37 and scored two tries for 6 points on his debut.

Match Report England vs. France

RUGBY LEAGUE FOOTBALL

Saturday 10th April 1937 Thrum Hall, Halifax.

England were flattered by the margin by which they beat France in the Rugby League International match at Halifax. They won by four goals and five tries (23 points) to three goals and one try (9 points).

France held their own in the matter of handling and speed, and the whole side exploited the Rugby code in a way which the crowd appreciated. By half-time France led by nine points to seven, but throughout the second half they were without Samatan, their wing three-quarter back, who dislocated a shoulder.

In spite of this handicap France held their own for a long time. England, indeed, were often in difficulties, but towards the end the loss of a player proved too much for France, who deteriorated, and England, rallying, scored freely.

On the whole the English team was disappointing. There were occasions when much of their play was ragged, and their crude movements compared unfavourably with those of the Frenchmen, who infused into their play much enthusiasm and skill.

The outstanding player of the match was Rousie, the French captain and stand-off half-back. He was fast and clever, and never neglected an opportunity to race off on his own or give his three-quarter backs chances with cleverly placed passes. In addition Rousie scored six of France’s nine points by kicking three goals – one wonderful dropped goal. Hodgson, the England captain, also played well. Belshaw was the best of the English backs. His steadiness and courage at full-back often saved England.

The Teams were:-

ENGLAND – B. Belshaw (Liverpool Stanley), back; B. Cunniffe (Castleford), F. Harris (Leeds), T. Winnard (Bradford Northern), and J. Cumberbatch (Broughton Rangers), three-quarter backs; Pepperell (Huddersfield) and T. McCue (Widnes), half-backs; H. Woods (Liverpoool Stanley), T. Armitt (Swinton), H. Higgins (Widnes), M. Hodgson (Warrington) (captain), J. Arkwright (Warrington), and H. Beverley (Hunslet), forwards.

FRANCE – M. Guiral, back; A. Cussac, E. Bosc/Bosch, Nogueres (F.) and B. Samatan (R.), three-quarter backs; M. Roussie (captain) and P. Brinsolles, half-backs; L. Griffard, Porra, Bruzy, C. Petit (C.), Claudel, and M. Bruneteau, forwards.

REFEREE – F. Peel (Bradford)

| England 23 | France 9 | |

| Tries – 3pts | J. Cumberbatch (2), T. Winnard (2), B. Cunniffe | M. Brunetaud |

| Goals – 2pts | M. Hodgson (3), T. Winnard (1) | M. Roussie (2) |

| Drop goals | M. Roussie |

International Career

Jimmy Cumberbatch won three England caps scoring in each of his matches a total of four tries for twelve points.

England vs. Wales

Saturday 29th January 1938 England 6 vs. Wales 7 at Odsal, Bradford

A crowd of 8,637 watched Wales beat by England by 9 points to 6. England were unable to overcome Wales’ 7 point half-time lead but finished strongly.

| England 6 (3 at half-time) | Wales 9 (7 at half-time) | |

| Tries – 3pts | J. Cumberbatch, B. Hudson | C. Evans |

| Goals – 2pts | J Sullivan (2) |

| Teams | England | Wales |

| Fullback | Walkington | J. Sullivan (c) |

| Wing | B. Hudson | B. Johnson |

| Centre | S. Brogden | C. Evans |

| Centre | J. Croston | G. J. Risman |

| Wing | J. Cumberbatch | A. Edwards |

| Five-Eighth | Shannon | O. Morris |

| Halfback | T. McCue | D. Jenkins Jnr |

| Front Row | H. Beverley | D. Prosser |

| Hooker | Booth | C. Murphy |

| Front Row | Ayres | L. Rees |

| Second Row | Irving | G. Morgan |

| Second Row | T. Armitt | N. Fender |

| Lock | H. Higgins | A. Givvons |

France vs. England

Sunday 20th March 1938 France 15 vs. England 17 at Stade de Paris, France

A crowd of 15,000 watched England beat France by 17 points to 15.

| France 15 (5 at half-time) | England 17 (7 at half-time) | |

| Tries – 3pts | M. Brunetaud, Salat, H. Sanz | T. Armitt, J. Cumberbatch, T. McCue |

| Goals – 2pts | M. Guiral (3) | B. Belshaw (3) |

| Drop goals | J. Arkwright |

| Teams | France | England |

| Fullback | M. Guiral | B. Belshaw |

| Wing | H. Sanz | J. Cumberbatch |

| Centre | C. Estoueight | J. Croston |

| Centre | M. Roussie | Morrell |

| Wing | Salat | Grainge |

| Five-Eighth | P. Brinsolles | Herbert |

| Halfback | J. Dauger | T. McCue |

| Front Row | A. Rousse | Ellarignton |

| Hooker | H. Durand | J. Arkwright |

| Front Row | L. Griffard | Ayres |

| Second Row | Gau | H. Higgins |

| Second Row | M. Nourrit | T. Armitt |

| Lock | M. Brunetaud | Thacker |

Club Career

Broughton 1937 F – Broughton Rangers based in Salford, Manchester.

Newcastle 1938 W

This live piece of mercury, who has come before the selectors as a Tour probable, first came to Manchester to play for Swinton, who passed him over. However, he signed for Broughton and has since proved their finest acquisition. His clever play on the Broughton left wing has also proved him to be one of the League’s foremost attackers. Born in Liverpool, he first played the Association game for his school until he became attached to barrow St. Matthew’s Club. Has earned his County Cap, and has also played for the League against France. Jimmy’s brother Val Cumberbatch, is a member of the Barrow Club, and two other brothers keep up the family tradition of excelling at sport. Jimmy is a good sport, a good player, and one of the the League’s most popular players.

RUGBY LEAGUE

Hull Daily Mail 29 October 1937

CUMBERBATCH SIGNS FOR NEWCASTLE

James Heywood Cumberbatch, the Broughton Rangers and Lancashire County left-wing three-quarter, has been signed by Newcastle, and will assist the north-eastern club against Liverpool Stanley to-morrow.

At [sic] native of Liverpool, Cumberbatch joined the Rangers from Barrow St. Matthew’s in season 1932-33 before the removal of the club from the Cliff to Belle Vue.

He gained Lancashire County honours in 1935 against Yorkshire, and in 1936-37 in matches against Yorkshire and Cumberland.

http://search.findmypast.co.uk/bna/viewarticle?id=bl%2f0000324%2f19371029%2f136

Family

James Haywood Cumberbatch was born 9 February 1909 in Liverpool, England. He was the son of Theodore Theophilus Cumberbatch, a ship’s steward, originally from Barbados and Mary Ellen née Kewin originally from Ramsey in the Isle of Man. He married Eva née Ball in 1936 and they had a son James. James’ brother Val Cumberbatch played rugby league for Barrow and he played one game for England.

Sources

- Match Report – The Times Monday, 12 Apr, 1937; pg. 6; Issue 47656; col C : Rugby League Football England Beat France (Sport)

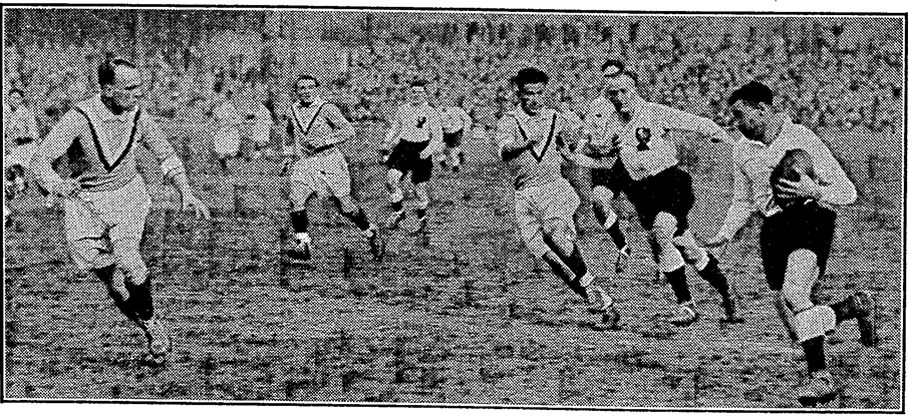

- England vs France picture in The Times Monday, 12 Apr, 1937; pg. 18; Issue 47656; col A

- The Rugby League Project

- Cigarette Card Sporting Events and Stars Series of 97 No. 74 J. Cumberbatch

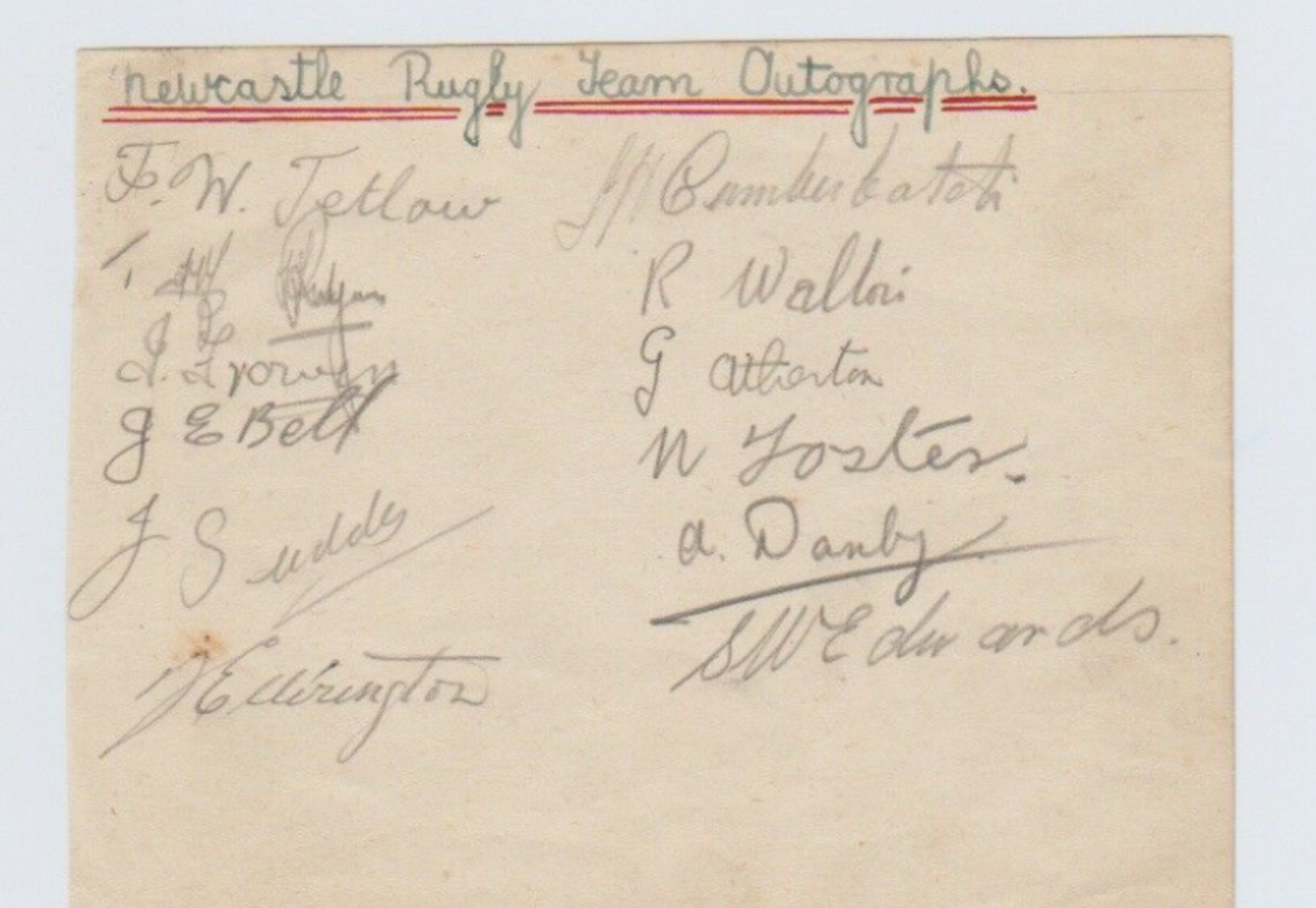

Newcastle Rugby League Football Club

Newcastle Rugby Team Autographs 1937-1938

Signed by:

- JW Tetlow

- T? Ryan?

- Ivor Frowen

- GE Bell

- Jack Suddes

- John Ellerington

- Jimmy Cumberbatch

- Dick Walton

- G Atherton

- Norman Foster

- A Danby

- Stan Edwards

BLAME NEWCASTLE FOR THAT!

with thanks to NCJ Media https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/

This is my crop of a photo taken on 3rd January 1938, and it subsequently appeared in the “North Mail and Newcastle Chronicle”. Jimmy (centre of the shot, facing the camera) was playing at number 5, on the wing, for Newcastle RLFC against Wakefield Trinity. Jimmy scored Newcastle’s only try of the match.

Also facing the camera are i) Ivor Frowen, Newcastle’s number 7 (scrum half), who is in the foreground but behind Jimmy, (to his left, on our right as we look at the picture), and ii) Jack Suddes (Newcastle hooker, number 9), between Jimmy and Ivor, but very much in the background. Jack is very blurred in that image but, having looked long and hard at this – and much clearer – pictures of him, I’ll be more than happy to take the blame if it ever turns out to be some else!

By Iain Robson 2013

Part Two

After my train had left the MetroCentre – the out-of-town shopping centre just south of the Tyne – I suddenly panicked. Those drawings approved by Mr. Bolton of Blaydon Urban District Council seventy-six years ago had shown a railway line going behind what was to become Newcastle RLFC’s second home ground.

And my train was on it.

Trying to spy a trace of something through the trees, my chance was gone as the trackside “site of the Blaydon Races” marker flew past. In any case, the stadium had been knocked down years ago.

But in the final paragraph of “Cherry & White” , the short book on Newcastle RLFC, John Proud asked: “ … how many of the players found a new team for the last season before World War 2? … And how many of them went on to serve in that conflict? …”.

It turns out the White City itself was requisitioned during the war to make camouflage netting. A letter to the owner dated 18th January 1944 refers to, “ … one or two defective floor boards in the Club room … ”.

Whoever typed the (unsigned) piece of paper advises that, “ … to avoid possible claims for damages should any worker catch her heel in holes … ”, they had, “ … asked Jackson to have them made secure” (‘Jackson’ seemingly the contractor).

Jack Suddes signed for Bramley on 10th December 1938, and his front row team mate, Dick Walton, went back to Castleford (his original club) for the 1939/40 season. And I was on the train to meet Jack Suddes’ son, John.

I arrived early at Hexham, the little stone-built station twenty miles west of Newcastle. And I wonder now if Dan McAvoy, Billy Brown and Beattie had come through here, coming across from Cumbria?

Or, unlike Iowerth Jones and Jim Turton, did they find work in Newcastle?

But when I wandered back to the station, I could see just a bit of Jack Suddes in the gentleman wearing the lightweight sweater, waiting outside. He gave me a lift to a café.

Mr Suddes was soft-spoken and careful, but in a friendly sort of way. And he was deeply proud of his dad. He didn’t spell it out in the daft way MasterChef contestants sometimes do. But sitting next to him, every now and then, you could sense it like heat coming off a coal fire.

Suddes! Here!

Mr Suddes had never seen a photo of Jack playing Rugby League, but he’d kept the 1930s contracts his dad signed with Newcastle and Bramley. After talking a bit of this and that, Mr Suddes remembered how Jack’s reputation as a hooker followed him to Grammar school, when a games teacher called out:

“Aww, you! Young Suddes! Come here!”

As well as winning trophies with Tynedale RU, running the All Blacks close with Northumberland & Durham RU ( “North Mail” match report the following day: “ … Suddes was almost complete master in hooking”), scoring Newcastle RLFC’s last ever try, grafting for Bramley and possibly becoming England RL reserve

hooker in 1939, Jack had also, as a boy, captained the team of little John’s new school.

Mr Suddes burst out laughing as he recalled:

“Well, I mean, even practice games: ‘Suddes! Here! Want to see you! Don’t let your father down!’ And I was getting hammered time and time again!

I asked if he’d played the same position as his dad:

“It started off there, yes. But, I mean, this was him, it was trying to replicate … I eventually graduated to the back row, thank God for that!”.

A little while later, I asked Mr Suddes if he thought life was maybe a bit narrower, but simpler, back in his dad’s day:

“I think people strived a lot more to get where they wanted to be. He was a prime example in that he wanted a house. He was in the joinery business and he worked for a builder – J.S. Emerson.

“But, I mean, they were working nearly five and a half days a week. He’d have to take some hours off before he got on the bus or a train to get to Bramley – you know, come back late on Saturday night, shattered.

“And then be back at work on a Monday, which, er, tremendous, really.”

In Some Measure

Mr Suddes later told me over the telephone that Jack worked as a policeman during WWII – at one point, ending-up in London. And I wanted to find out about the other players, too.

And, after asking around, Westoe RFC put me in touch with someone who’d met Lenny Clough.

According to John Proud in “Cherry & White” , the winger had been the “man of the match” in the seven-all draw against Leigh on Christmas Day, 1936. Then, on p.27 of that book, John Proud wrote that Lenny, “ … who’d had such a promising opening to his Rugby League career, announced he had taken up a position in the Midlands and would no longer be available for selection … ”.

That was at the beginning of Newcastle’s second season in 1937. But Harold Yeoman, now ninety-two years of age, explained to me over the ‘phone that he’d watched Lenny play before he’d joined Newcastle (when he Lenny was a Westoe winger).

Later, in the RAF, Mr Yeoman crossed paths with him again. Lenny, by Mr Yeoman’s account, sounded like good company in uniform – apparently happy to share a beer and, to use Mr Yeoman’s words, he “put it down in some measure”.

Mr Yeoman then told me how, on 28th September 1942, Lenny took off from RAF Mildenhall on a mission to the Dortmund-Ems canal in Germany. Several hours after take-off, Lenny’s plane was hit by a Focke-Wulf 190 and, as Mr Yeoman went on to say:

“ … crashed 18:02 into the IJsselmeer, 8km south of what in 1942 was the island of Urk … Flight Sergeant Clough was last seen, using a fire extinguisher, bravely trying to put out the fire that was raging inside the fuselage. He has no known grave … ”.

Mr Yeoman had seamlessly gone from recounting personal experiences to reading from p.228 of

“Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War “ , Volume III, by W.R. Chorley.

Casualty details on www.cwgc.org indicate Lenny was thirty-one years of age, and survived by his mother, father and wife, Marjorie.

Rising Sun

A gentleman who works at the shop where Basil Liddle sold carpets (it trades under a different name now) put me in touch with Basil’s nephew, Stewart McKenzie. Basil, of course, had been Jack’s team mate at League and Union.

When I telephoned Mr McKenzie, I was keen to learn a bit about the Newcastle RLFC half-back’s personality:

“I think he was quite a ladies’ man, from what I can gather. But there wasn’t much said about that [laughs]. “According to me mother he would always try and be immaculate, when he went out. ‘Cause he had to be, sort-of, tidy and clean and well-shaven and nice hair combed. “So, he used to look after himself, I suppose.” Mr McKenzie explained that he was too young to get to know Basil personally. So I asked how his uncle was talked about among older family members: “Just that he was – whatever he did, he had to do well. He had to be, sort-of, the best. “You know, he was really into it. He really, sort-of, tried to be as good as he could. No matter what it was he did. Mr McKenzie told me a story from 1944, when a thirty-four year old Basil Liddle, who’d been stationed with the Royal Artillery down south, making Lance Bombardier, was back up in his native North Shields: “Me mother said he was walking along the road, and you’d think he was drunk, yet he didn’t drink. It’d be after tea time, because me grandfather came in from work and, er, his brother came in from work – so that would be after five o’clock. “So it’ll be about half-past five. They just thought they’ll take him up a cup of tea and, er, he was dead in bed. According to Mr McKenzie, Basil had spent time in the Scaffold Hill isolation hospital – about half-way between Newcastle and the coast, near the old Rising Sun pit (now a country park).

Although Mr McKenzie wasn’t sure, he suspects Basil may have been discharged from the Army due to ill health. The cause of death was TB.

Back in the café, I mentioned the manner of Basil’s passing to John Suddes:

“Yeah, well, it was rampant in those days, TB. I mean, they had the hospital along here, Wooley Sanatorium, and all my family had it.

“I had it. Me mother died of it. My father got it.”

I wondered if the lives of two Newcastle RLFC players been taken by something we get a routine vaccination for now. I asked Mr Suddes if Jack had died of TB, too:

“I couldn’t put my finger on and say ‘yes’. But it was, obviously, it was there. ‘Cause he spent time up in Wooley Sanatorium. He had about, I think, nine months up there and came back.

“And, speaking from experience, once you get TB, you know you’ve got it.”

Ships and Seaports

In the side office on the industrial estate, Mr Craven told me that, after Newcastle RLFC folded, Don probably played Rugby Union again under a false name. (Perhaps using his forename, Donald, as a surname.)

He’d apparently continued with his job as a machine operator throughout WWII and, come retirement at sixty-five, Don was employed as a conductor on British Rail restaurant cars.

It seems Don didn’t go straight from the factory job to the railways, though. Mr Craven mentioned that his dad also worked in hotels:

“One of his nephews was a steward for Cunard on the cruise ships, and I think they made a fair bit of money. You know, in those days, tips were – if you were in the right hotel, you could make a fair bit of money.

“And I think that was the attraction.”

“His running and his rugby subsidised his wages. But then, when he couldn’t play anymore, he found that the factory job wasn’t as rewarding as he needed it to be. And he found that that side of it was better paid.”.

And another one of Don’s nephews, David, cross-coded to Halifax RL in the 1945/46 season.

But working at sea was also a factor in Jimmy’s life – as Bob Cumberbatch of www.cumberbatch.org told me by e-mail:

“Jimmy at some point moved to 201 Wingrove Avenue, Newcastle-on-Tyne and in 1946 he was in the merchant navy as a fireman – i.e. he fed the boiler with coal.

“He probably served in the merchant navy during WWII and this might explain why I cannot find any brothers or sisters for their son James. My guess is that Jimmy and Eva probably did not have the time to expand their family during the war years”.

And Mr Craven recounted how Don went to see his nephew (who was playing for Halifax RL) in February 1949, after David was injured in a match against Workington:

“My father was with with him when he died. Me father was actually in his hospital room when he, when he actually passed away.

“He asked to be made more comfortable, and someone moved him. And he just, he literally took his last breaths as he was being moved, ye knaa?”.

According to Andrew Hardcastle of Halifax RLFC, David Craven had his neck dislocated during the Saturday match, then passed away the following Thursday.

In his introduction to “Cherry & White” , John Proud recalled how his school friends in the North East talked about the funeral “shortly after the event” (though he remembered the name as ‘Peter’, rather than David).

Around this time Don apparently played his last game of rugby – although Mr Craven couldn’t be sure if it was League or Union. And he told a story about the evening his dad came home from his final match:

“My mother said they literally had to cut his trousers off – his knee was so badly swollen. And there was no question of any treatment or anybody taking responsibility. I mean, he was left to get on with it.

“He was virtually, a cripple’s the wrong word but, you know, he walked with great difficulty for the rest of his life, after his rugby career.

“And it was down to injuries, knee injuries.

Public Speaker

During his BR days Don became, according to Mr Craven, active within the Newcastle Branch of the National Union of Railwaymen:

“He was the secretary – spoke at conferences and all sorts. In fact, to be honest, he probably could have done better for himself. He was very much a strong trade unionist.

“My mother often said he was offered a job in London, and he turned it down because it meant he had to resign from the union and become part of the management. He was that staunch, that his principles wouldn’t let him.

“He could have had a much better lifestyle himself later on, by being in management. But it meant compromising his beliefs in the union.

“I never heard him, but my mother said he was a fabulous public speaker. He could go to conferences and stand up without any notes and talk for twenty minutes. And he was quite an intelligent guy himself, if the truth be known.”

And, although Mr Craven speaks with a North East accent, he later told me that Don – who lived in Rowlands Gill, County Durham – spoke with a Yorkshire accent and was originally from Leeds.

Gretna Green

Mr Craven could remember giving his father lifts to local NUR meetings in the 1960s And one Castleford fan, who preferred not to be named, told me that during the same decade Dick Walton – who had packed-down forty-nine times alongside Jack for Newcastle – had a falling out with his son, Dougie.

So I telephoned Geoff Smith, of the Castleford Player’s Association. And Mr Smith told me:

“Basically, what happened – he’s only a teenager, fell out with his dad over the girlfriend, so he’s shot off to Gretna to get married. That annoyed his father even more.

“And then he got picked for Great Britain – still only a teenager. The publicity that followed was that his dad didn’t go to the match to see him play for Great Britain against France.”

Mr Smith also said:

“They were only a couple of kids at the time. But, let me tell you – I mean, Dougie’s sadly died not all that long since. And Dougie, and his teenage girlfriend that he eloped with, were still the best of friends ’til the day he died.

“Little fairytale.

“I mean, his Dad fell out with him ’cause he didn’t think it were gonna last, and it lasted right up ’til the very end.”.

And it turns out that the end came for Dick’s son the very month I began researching Newcastle RLFC. But the Castleford fan who tipped me off sang Dougie’s praises, describing him as “a smashing lad”, and that, on the pitch, “he took everybody by storm”.

The same fan described Dick as a “well-known character” in the homes surrounding the Castleford ground. And when I asked about the playing reputation of Jack Suddes’ front row team mate – sent-off playing for Newcastle against his old club in 1936 – my source said:

“Oh yeah, he were a big, hard … you know, they talk about tough and what not not these days, but they were brutal then, I would say.”

1972

Over the telephone, Judy Cumberbatch cheerfully remarked that Jimmy was “probably more of a man’s man” than his son, although she described them both as the “quiet gentleman” type.

Mrs Cumberbatch explained that Jimmy’s son, who also went to sea, played pedal steel guitar in a band. Jimmy apparently had remained in the Merchant Navy, and “used to come to the venue to meet him when he was home from leave”.

Mrs Cumberbatch also said she had no more than a few opportunities to speak to Jimmy:

“When I met my husband, Jim, who was their only son, he only ever saw his father when he came home on leave. And it was while he was home on leave that he did die”.

According to Mrs Cumberbatch, he separated from his wife, Eva, in the mid to late 50s. And Mrs Cumberbatch didn’t marry Jimmy’s son until after the former Newcastle and England player had passed away.

“It was sudden, you know, it was sudden. I’m not sure if they knew he was home from leave, actually, this particular time”.

Jimmy was apparently staying in Newcastle lodgings then. And when I telephoned his grandson, Jamie Cumberbatch, he told me Jimmy may have lost his eyesight shortly before the end came (in the early months of 1972):

“I thought me dad meant that he went blind sort-of leading up to when he passed away. But I think me mam was saying that he went blind through one of the issues that he had – basically on his last few days”.

Early Bath, Blood Bath

In his introduction to “Cherry & White” , John Proud, referring to North East Rugby Union in the old days, wrote:

“ … Lots of working class lads played the game and some of the teams were part of a factory or colliery welfare set up. I can remember, as a raw teenager, being persuaded to join Winlaton Vulcans in the kitchen of a council house on the Hanover Estate. Our prop forwards arrived for the match, eyes still rimmed with coal dust, straight from the foreshift at the Mary and Bessie Colliery. How they loved to play the Old Boys teams. Now that really was class warfare …”

That incident occurred within fifteen years of Newcastle RLFC folding. But, separately, Mr Craven told me that Don was “always fairly critical of the snob value of Rugby Union in those days”, and that “he preferred the people he met in Rugby League.”

Seghill RFC is the North East RU club that produced Stan Edwards and John Ellerington – not to mention Kenny, the half-back who played against Newcastle for Jimmy’s old club, Broughton Rangers, on 27th April ’38.

I wasn’t able to track down John or Stan’s relatives but, a year or so after Jimmy died, George Arnott began playing for their club. And, today, Mr Arnott is Seghill chairman. And I read that quote from John Proud’s book to Mr Arnott over the phone.

Thinking of the “snob value” Mr Craven mentioned, and of those harsh old Rugby Union attitudes and laws about what clubs and players were (not) supposed to do, I wondered how things had really played out on the ground. On North East grounds – at clubs like Seghill.

And, among other things, Mr Arnott said:

“Where you had, I would say, the public school connection – we always refer to them as ‘the other clubs’ – where you had that public school connection, you did have that kind of attitude.

“Literally, until the mid fifties, I would say 90% of the team were made up of people who worked in the collieries. When the pit closed in the 60s people came to the club from Tyneside and South-east Northumberland.

“Like, Blaydon, Winlaton, Ryton, Ashington. You know, Blyth, clubs like that. Chester-le-Street, Washington – you can go through all the clubs that have been linked to some kind of pit thing.

“I can remember teams from Armstrongs, the works on Scotswood Road, they had a team. Smith Docks at North Shields had a team. Me dad’s old factory in Hebburn, Reyrolles – they had a rugby team.

“There was a lot of working class rugby teams around the North East.

“I’m almost sure I can remember a northern Rugby League side photograph in the old clubhouse.

“I would imagine there will be certain clubs, and mostly your county committees are full of representatives of these type of clubs, that’s where you get the feeling from that they don’t like this cross-code, you know?”

While researching these articles, I’d been told a tale about how, in the 1960s or 70s, a player who’d crosscoded to League went back to the North East club where he’d started out.

After some individual ‘spotted’ him having a pint with his old RU team mates, the story goes that the general emotional response was somewhere between ‘so what?’ and ‘what you gonna do about it?’.

But in the North East that Newcastle RLFC left behind, did the stereotypical differences of class and snobbery that many might expect to find, dividing League from Union, exist instead within North East rugby itself?

And perhaps that was already the case when Alfred Peel went to the Rugby League, or John Wilson came to the County Hotel, in 1936?

Something else Mr Arnott said was:

“When I joined the club, there was a general feeling that there were certain clubs, who, erm, thought themselves way above anybody else. And that if you played for a club like ours, you weren’t worth knowing.

Mr Arnott also remarked that he’d played alongside six men who, in his opinion, had the ability to play at the “top level”. But only one of them went on to do so.

So I asked if he thought the others might not have gone as far as they might have because they weren’t the ‘right people’:

“Oh yeah. I mean they were constantly being poached by the better clubs – the so-called better clubs – in the 60s, 70s and 80s. And it caused a lot of bad feeling.

“When we used to play these ‘other clubs’, I mean, it was a blood bath. Y’know, nowadays it would be probably fifteen, thirty players standing on the touch line banned.

“They think we’re not as good as them, so let’s just show them that we are, you know?

“And it still goes to this day”.

The Old Days

While discussing rugby from times past with Harry Edgar, editor of the “Rugby League Journal” , I was wondering if class lines had gone through, rather than around, the North East rugby scene Newcastle RLFC left behind. I mentioned Mr Arnott’s list of pit teams. And I was interested in the idea of players not getting picked because they weren’t the ‘right people’.

Mr Edgar didn’t feel that such things had been limited to the North East. And he also said:

“I think, actually, it’s a really interesting thing. ‘Cause people have this thing about, ‘Oh, Rugby League, Rugby Union, class differences’, and it’s fair enough.

“But, of course, this only manifested itself in the areas where Rugby League existed, to be honest. Which are only basically three counties – Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cumberland.

“In other parts of the country, I don’t think there was prejudice against Rugby League, it was just total ignorance. Nobody really knew what it was. It wasn’t that people had this thing about it, it just wasn’t an issue, you know?

“So you find that the most virulent anti-Rugby League people tended to be in Lancashire, Yorkshire and Cumberland – because there they really had a rival.

“And, of course, they didn’t like it.”

Stuff Your Rugby Union

Back in the café with Mr Suddes, it was getting close to closing time.

Apparently, for Jack, Tynedale RU was always his club – the team he’d played for since leaving school and, as Mr Suddes said, “all his friends and everything”.

I’d already been told that Jack attended Tynedale matches later in life, so I asked Mr Suddes to tell me about it:

“He was banned.”.

Mr Suddes drew out the word a little, to take the mickey.

“He was invited to join the committee. And he was told, no, you couldn’t come into the club house, you’re a Rugby League man.

“This was a directive from the Rugby Union but – I take me hat off to the rugby club, anyhow – they said stuff your Rugby Union, he’s coming. They took him in. I mean, he was well into his forties, I’d imagine, then.”

I asked Mr Suddes if he remembered Jack ever saying anything about that.

“No, he wouldn’t. He was a man would just, er, take it, not say anything. It would be there. This was the way he’d play rugby, though.

“Somebody, they could hit him once, he wouldn’t say anything. The next time, he would hit him, you know? Payback time, yeah.

“And it was the same with that, the same with everything that happened to him. He’d absorb it BUT he’d remember it.”

Time on the Clock

Newcastle of the 1930s was a different place to the cleaned-up city centre we know today. The North Easterners listening to Alfred Peel’s second-half radio commentary from Byker knew a different Rugby League to the game we watch on Sky these days.

But when fans in the heartlands defend their game, or when Geordies defend their city, the changes aren’t so big that there’s nothing left to recognise.

By putting things in to, or leaving things out of, these articles – for space, to ‘engage the reader’, to catch the eye – I was wary of serving-up a fact-peppered fiction: something that’s to your taste and mine because of things we think we know today, when maybe we don’t.

One thing is writing to a deadline; another is living with what you’ve written once the deadline is met.

Take that reporter who said that Suddes, Cumberbatch, Liddle, Luckey, Edwards, Ellerington and Taylor had become “the forgotten men of rugby league” in 1938. Whatever the flaws and limits of my articles, perhaps I can now suggest that he spoke at least seventy-five years too soon?

For Jack, Jimmy, Basil, J.B., Stan, John, Bob and Lenny; not forgetting Dick and Don the Yorkshire, and all the rest.

Gan canny, lads.